In Eastern European Russia, mid-way between Moscow and the Ural Mountains, lies the region known as the ‘Volga Bend’. Here, the mightiest river on the European continent executes a dog’s leg turn, altering the direction of its flow from eastward to southward. In the process, it happens to traverse a narrow band of country in which the climate is sufficiently mild to produce conditions similar to those of north-western Europe. Here, settled farming communities have eked out a living from the earth and the forest for millennia, living a lifestyle very similar to that of our own ancestors; one quite distinct from that of their neighbours, the nomadic hunters of the northern woodlands and herders of the steppes.

The ethnic groups that inhabit this region are diverse and, often, exotic. Russians today form the majority; but also of particular significance are the Tatars, descendants of the Turkic tribes that accompanied Genghis Khan and his Mongols across Eurasia, and lorded it over Russia for centuries. Their ancient capital, Kazan, once a rival to Moscow itself in the politics of the region, lies at the heart of the Volga bend. Another ethnos is the Chuvash, a unique people speaking the last known language similar to those of the Huns and Khazars.

Perhaps the most unusual of all the peoples in the region, however, are the Mariy. They are not a large nation, numbering only around 600,000; nor are they particularly important in the eyes of history, since they have never had their own independent, centralised state. What does makes them special is their religion. This is not Islam, as in the case of the Tatars and Bashkirs to the east, nor Orthodox Christianity as among the Russians, Mordvin and Chuvash. Rather, many of them follow an ancient form of autocthonous paganism, which seems to have been the religion of the people since their initial ethnogenesis. As such, they are one of a very few peoples in the world today who can be described as a ‘heathen nation’; a term here defined as a settled, technically advanced people who have preserved their ancient religion from destruction.

The Mariy live, today, scattered across the entirety of the Volga Bend region as far east as the Urals. Their numbers are greatest on the left bank of the Volga between Nizhniy Novgorod and Kazan; the region today known as ‘Mariy El’, Mariy-Land in the native tongue. The inhabitants of Mariy-El are known as the Meadow Mariy. A smaller community, more fully assimilated to the Russian cultural mainstream, lives on the opposite bank of the Volga; these are called the Mountain Mariy. In the approaches to the Urals resides a third grouping, called the Eastern Mariy on account of their geographical distribution.

Linguistically, they are a part of the Uralic language family; a grouping that includes the Finns, Estonians, and Hungarians, along with a long list of less well-known peoples that live scattered from the western border of Russia to the depths of Siberia. Their culture shows, materially, influences from both the Slavic nations of Europe and the Turkic peoples of the Asian steppe, along with components shared with other nearby Uralic peoples that may be regarded as, if not native, at least of ancient origin.

The material culture of the Mariy is simple, designed to service the needs of a people engaged in farming, hunting, and harvesting the forests. The absence of a native elite throughout most of their history has kept Mariy culture from indulging in the artistic forays seen in many other cultures- instead, folk art remains the predominant tendency. Clothes are simple but colourful, making strong use of the shade of white. Wood-carving is probably the principal craft; since forests dominate the region of their habitation, wood forms the principal medium from which craft goods are shaped, and from which buildings are constructed.

The importance of the forests in the culture of the Mariy is difficult to under-emphasise. The forests provided a source of meat separate from the herds, allowed the collection of furs and honey valuable in trade, and gave the people a refuge in times of danger. So close is the bond that the Mariy in fact refer to themselves as ‘the Little People of the Forest’, many claiming descent from forest animals converted into supernatural beings.

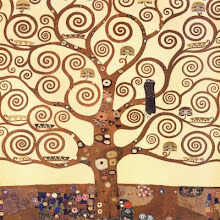

Naturally, the importance of the forests extends deeply into the religion of the Mariy. There are no grand sacred structures in their religion; no pagan temples or churches. Instead, communal worship is conducted in sacred groves, as was the case throughout much of pre-Christian Europe. It is estimated that there are around 360 such sacred groves scattered across Mariy territory.

The sacrosanctity of the groves often stems from the belief that a particular tree located within its perimeter is the place of residence of a local deity. Alternatively, the tree may be home to the spirit of a hero or ancestor who lies buried beneath it, and part of whose soul has taken up permanent residence in the tree above. A mixture of the two is also normal; gods or divine animals are often seen as the ancestors of men, and human heroes, as in ancient Greece, can attain to divine status. The boundaries between the human and supernatural worlds, and between the human and animal worlds are not as fixed as in western culture. Ancestral connections are one of the main holds the groves have upon the Mariy; families will often commemorate their connection to particular groves, and will travel to visit them when possible.

The form taken by worship is described as ‘collective prayer’, or ‘offering’. It involves the assembly of a number of Mariy, sometimes numbering up to the thousands. Prescribed prayers and incantations are chanted by the presiding priest, known in the Mariy language as a Kart. The Karts are ordinary Mariy who live among the people. They are permitted to marry, and are little distinguished from the great mass of the people; a trait that has allowed them to survive the long centuries of persecution. There has been, traditionally, no hierarchy or organisation among the Karts, though this is changing in the present day, and claimants to the title of Archkart are currently competing with one another for support amongst the community.

The ethnic groups that inhabit this region are diverse and, often, exotic. Russians today form the majority; but also of particular significance are the Tatars, descendants of the Turkic tribes that accompanied Genghis Khan and his Mongols across Eurasia, and lorded it over Russia for centuries. Their ancient capital, Kazan, once a rival to Moscow itself in the politics of the region, lies at the heart of the Volga bend. Another ethnos is the Chuvash, a unique people speaking the last known language similar to those of the Huns and Khazars.

Perhaps the most unusual of all the peoples in the region, however, are the Mariy. They are not a large nation, numbering only around 600,000; nor are they particularly important in the eyes of history, since they have never had their own independent, centralised state. What does makes them special is their religion. This is not Islam, as in the case of the Tatars and Bashkirs to the east, nor Orthodox Christianity as among the Russians, Mordvin and Chuvash. Rather, many of them follow an ancient form of autocthonous paganism, which seems to have been the religion of the people since their initial ethnogenesis. As such, they are one of a very few peoples in the world today who can be described as a ‘heathen nation’; a term here defined as a settled, technically advanced people who have preserved their ancient religion from destruction.

The Mariy live, today, scattered across the entirety of the Volga Bend region as far east as the Urals. Their numbers are greatest on the left bank of the Volga between Nizhniy Novgorod and Kazan; the region today known as ‘Mariy El’, Mariy-Land in the native tongue. The inhabitants of Mariy-El are known as the Meadow Mariy. A smaller community, more fully assimilated to the Russian cultural mainstream, lives on the opposite bank of the Volga; these are called the Mountain Mariy. In the approaches to the Urals resides a third grouping, called the Eastern Mariy on account of their geographical distribution.

Linguistically, they are a part of the Uralic language family; a grouping that includes the Finns, Estonians, and Hungarians, along with a long list of less well-known peoples that live scattered from the western border of Russia to the depths of Siberia. Their culture shows, materially, influences from both the Slavic nations of Europe and the Turkic peoples of the Asian steppe, along with components shared with other nearby Uralic peoples that may be regarded as, if not native, at least of ancient origin.

The material culture of the Mariy is simple, designed to service the needs of a people engaged in farming, hunting, and harvesting the forests. The absence of a native elite throughout most of their history has kept Mariy culture from indulging in the artistic forays seen in many other cultures- instead, folk art remains the predominant tendency. Clothes are simple but colourful, making strong use of the shade of white. Wood-carving is probably the principal craft; since forests dominate the region of their habitation, wood forms the principal medium from which craft goods are shaped, and from which buildings are constructed.

The importance of the forests in the culture of the Mariy is difficult to under-emphasise. The forests provided a source of meat separate from the herds, allowed the collection of furs and honey valuable in trade, and gave the people a refuge in times of danger. So close is the bond that the Mariy in fact refer to themselves as ‘the Little People of the Forest’, many claiming descent from forest animals converted into supernatural beings.

Naturally, the importance of the forests extends deeply into the religion of the Mariy. There are no grand sacred structures in their religion; no pagan temples or churches. Instead, communal worship is conducted in sacred groves, as was the case throughout much of pre-Christian Europe. It is estimated that there are around 360 such sacred groves scattered across Mariy territory.

The sacrosanctity of the groves often stems from the belief that a particular tree located within its perimeter is the place of residence of a local deity. Alternatively, the tree may be home to the spirit of a hero or ancestor who lies buried beneath it, and part of whose soul has taken up permanent residence in the tree above. A mixture of the two is also normal; gods or divine animals are often seen as the ancestors of men, and human heroes, as in ancient Greece, can attain to divine status. The boundaries between the human and supernatural worlds, and between the human and animal worlds are not as fixed as in western culture. Ancestral connections are one of the main holds the groves have upon the Mariy; families will often commemorate their connection to particular groves, and will travel to visit them when possible.

The form taken by worship is described as ‘collective prayer’, or ‘offering’. It involves the assembly of a number of Mariy, sometimes numbering up to the thousands. Prescribed prayers and incantations are chanted by the presiding priest, known in the Mariy language as a Kart. The Karts are ordinary Mariy who live among the people. They are permitted to marry, and are little distinguished from the great mass of the people; a trait that has allowed them to survive the long centuries of persecution. There has been, traditionally, no hierarchy or organisation among the Karts, though this is changing in the present day, and claimants to the title of Archkart are currently competing with one another for support amongst the community.

While the Karts conduct the ceremonies animals, birds, grain and trinkets are sacrificed to the gods of the holy place in the manner the priest decrees. Sacrificed animals are then cooked and eaten in a communal feast, accompanied by the singing of songs and consumption of alcohol. As such, the collective prayer serves as an excuse for celebration of family and ethnicity, along with the opportunity to indulge in the eating of meat; something which, in peasant economies, is generally reserved for special occasions.

The idea of animal sacrifice is worth commenting on; involving, as it does, the taking of animal life, it is a practice that often appears unpalatable to the people raised in western cultures. It is worthwhile bearing in mind, therefore, that, for an agricultural people such as the Mariy, having meat to celebrate a special occasion necessarily involves the taking of animal life. This is, of course, also the case with Christmas turkey. The Mariy simply happen to perform a ritual to sanctify and dedicate the meat while killing it, rather than hiding the act away the way we do and celebrating the carcass afterwards. In the end result, the only difference is one of human cultural niceties; from the turkey’s viewpoint, the outcome is the same either way.

So what, and who, are these bloodthirsty gods worshipped in the groves? There is no standard enumeration; deities are often local or regional, holding sway over a certain region, or only honoured by a specific grouping of people. The major deities, however, are respected by all the people. The foremost of these is the ‘Great God’, Kugu Yumo, an ancient deity who somewhat resembles the god of the monotheistic faiths. He is seen as all-knowing and all-seeing; though these attributes, it should be noted, are also attributable to pre-Christian deities such as Odin in Scandinavia, who could see the whole world by means of his raven messengers. He was also involved in the creation of the world. He is honoured, being mentioned along with his most prominent helpers, in daily prayers; but is not the sole, or even primary, focus of Mariy religiosity.

So what, and who, are these bloodthirsty gods worshipped in the groves? There is no standard enumeration; deities are often local or regional, holding sway over a certain region, or only honoured by a specific grouping of people. The major deities, however, are respected by all the people. The foremost of these is the ‘Great God’, Kugu Yumo, an ancient deity who somewhat resembles the god of the monotheistic faiths. He is seen as all-knowing and all-seeing; though these attributes, it should be noted, are also attributable to pre-Christian deities such as Odin in Scandinavia, who could see the whole world by means of his raven messengers. He was also involved in the creation of the world. He is honoured, being mentioned along with his most prominent helpers, in daily prayers; but is not the sole, or even primary, focus of Mariy religiosity.

Beneath Kugu Yumo comes a pantheon composed of the spirits of important physical objects, such as the gods of the sun, of the wind, of the forests and of the fields. Also included are the gods of important concepts, such as fate, oaths, and creative energy. As such, the religion is essentially animistic, attributing personalities to all the things of the world with which people will be required to relate, and allowing them to interact with these spirits by means of sacrifice. Animism can be understood as a religion based on the idea that all things- human, animal, or even inanimate- possess a discrete soul, or spirit. There are, in most enumerations, nine higher gods beneath Kugu Yumo; though the exact identities of these deities show some variation from list to list.

Religions to which the Mariy religion can be most easily compared include Japanese Shinto and Indian Hinduism. Shinto is also a survival of animism into the modern era, basically constituting the worship of nature. Where it differs from the Mariy faith is in the standardised, unitary nature of its pantheon, cemented by centuries of nationalist ideology. The diversity of Mariy deities more effectively mirrors the situation found in Hinduism, where an enormous number of local spirits are worshipped without the diversity threatening the unity of the religion over-all.

This, then, is the basic shape of the Mariy traditional religion. It exists both as a pure religion in its own right, and also mixed with Christianity to various degrees in syncretistic hybrid cults. There also exists a current within the Mariy religion, most effectively expressed in the writings of Popov and Tannygin (the latter himself a Kart), that is attempting to introduce a mystical schema similar to that found in some outside traditions into Mariy religion. In their presentation, the higher gods are viewed as hypostases of Kugu Yumo, who is seen as an emanational force under-pinning existence in a fashion reminiscent of the role attributed to Vishnu or Shiva in sections of Hindu tradition, or even of the neo-Platonic thought of late Roman paganism. While this tradition represents a modern intellectualisation of Mariy tradition, it is, nonetheless, an authentic outgrowth of that tradition and must, as such, not be dismissed out of hand. It may, if its creators succeed in their mission of standardising the faith, represent the future of Mariy religion.

So what, then, does the future hold for Mariy heathenism? The present situation of the Mariy people is, in many ways, a difficult one. They are currently a minority even in their titular homeland, the Mariy-El republic. The administration of that region is currently in the hands of the party of radical Russian Nationalist Vladimir Zhirinovsky, a man whose ideology includes a mixture of the fascist and the bizarre. As such, the human rights position in Mariy-El is far from ideal; in May 2005, the European Parliament even went so far as to pass a resolution sharply criticising Russia for the lack of basic rights accorded to the Mariy people. Activists in Mariy cultural organisations have been beaten up, and the previously mentioned Kart Vitaliy Tannygin has been arrested and imprisoned for allegedly promoting religious discord.

So what, then, does the future hold for Mariy heathenism? The present situation of the Mariy people is, in many ways, a difficult one. They are currently a minority even in their titular homeland, the Mariy-El republic. The administration of that region is currently in the hands of the party of radical Russian Nationalist Vladimir Zhirinovsky, a man whose ideology includes a mixture of the fascist and the bizarre. As such, the human rights position in Mariy-El is far from ideal; in May 2005, the European Parliament even went so far as to pass a resolution sharply criticising Russia for the lack of basic rights accorded to the Mariy people. Activists in Mariy cultural organisations have been beaten up, and the previously mentioned Kart Vitaliy Tannygin has been arrested and imprisoned for allegedly promoting religious discord.

A further challenge comes from the resurgent Christian religion. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, evangelical protestant missionary groups have attempted to make inroads into remnant pagan populations. They have a presence in Mariy-El at the moment, though their mission has not yet met with extensive success. The Orthodox Church of Russia, too, is making its presence felt; Bishop Ioan of Yoshkar-Ola has criticised modern Mariy religious gatherings as ‘occult perversions of traditional paganism’.

The extent to which the other religions of Russia are able to act against Mariy paganism is, however, limited by the terms of the 1997 law on religion. This legislation states that religions ‘constituting an inseparable part of the historical heritage of Russia's peoples’ must be respected. More, it specifically includes among such religions ‘ancient pagan cults, which have been preserved or are being revived in the republics of Komi, Mari-El, Udmurtia, Chuvashia, Chukhotka and several other subjects of the Russian Federation.’ Due to the terms of this legislation, Orthodox priests decrying the Mariy religion are subject to imprisonment. They would, in fact, have committed the same offence for which Vitaliy Tannygin was arrested. The argument of Tannygin’s accusers was that he over-stepped the very mark that in other circumstances protects the Mariy, claiming his religion was superior to all others, and potentially exacerbating religious-ethnic tensions in Mariy-El.

The legal situation thus ensures that dealings between religions are forced to retain a degree of mutual respect and toleration. Whatever may be said of the character of the provincial government, or the state of human rights in Russia in general, it must be admitted that such legal protection means that the situation for the Mariy heathen religion is currently better than it has been at almost any time in the last few centuries. Under Communism, Mariy religiosity was repressed by the prevalent state ideology of atheism. Under the rule of the preceeding Tsarist regime, Orthodox Christianity was the state religion, and forced baptism campaigns were conducted against the Mariy. The people were forced to pay for the upkeep of churches in which they did not wish to worship, and faced imprisonment and deportation to Siberia if they were caught practicing their native traditions. This is now, definitively, no longer the case.

So will the Mariy religion experience a resurgence in the new, liberal environment? Not if it does so by attaching itself to an anti-Russian, nationalist agenda. The legal protection that has been given can easily be removed, should the Russian state deem it in its interests to do so. It is well-known that the Russian government is hostile to separatist nationalism in its constituent republics, as Chechnya has so amply proven. On the other side of the coin, stoking up the fires of nationalism could help to breed an environment of inter-communal hostility that might, given time, transform the ethnic mosaic of the Volga Bend into a northern version of the Balkans. Such an outcome is, from all perspectives, one to avoid.

So what is the alternative? In many countries, different religious traditions have a long history of co-existence; in China, Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism have rubbed along side-by-side since the first millennium; and in Egypt Islam and Coptic Christianity have maintained peaceful relations since the 7th century Arab conquest. If mutual respect between traditions can be maintained, there is no reason that the religions of the region cannot all survive. If this is the case, then the unique tradition of the Mariy may yet prove a resource for that people to deploy in their efforts at future development. It is easy to imagine tourist interest arising in the sacred groves, and curiosity on the wisdom of the Karts arising in lands further west. If such potential can be translated into actual visitors and the arrival of tourist dollars, then the poverty that blights the republic of Mariy-El could be, in part, alleviated. It would be a wonderful thing indeed if the oldest, most repressed parts of the Mariy culture could be the engine that drives their future economic salvation; whether this will be so is in the hands of the Mariy themselves, of any westerners willing to trail-blaze the region, and, as the Karts might remind us, of the gods.

The idea of animal sacrifice is worth commenting on; involving, as it does, the taking of animal life, it is a practice that often appears unpalatable to the people raised in western cultures. It is worthwhile bearing in mind, therefore, that, for an agricultural people such as the Mariy, having meat to celebrate a special occasion necessarily involves the taking of animal life. This is, of course, also the case with Christmas turkey. The Mariy simply happen to perform a ritual to sanctify and dedicate the meat while killing it, rather than hiding the act away the way we do and celebrating the carcass afterwards. In the end result, the only difference is one of human cultural niceties; from the turkey’s viewpoint, the outcome is the same either way.

So what, and who, are these bloodthirsty gods worshipped in the groves? There is no standard enumeration; deities are often local or regional, holding sway over a certain region, or only honoured by a specific grouping of people. The major deities, however, are respected by all the people. The foremost of these is the ‘Great God’, Kugu Yumo, an ancient deity who somewhat resembles the god of the monotheistic faiths. He is seen as all-knowing and all-seeing; though these attributes, it should be noted, are also attributable to pre-Christian deities such as Odin in Scandinavia, who could see the whole world by means of his raven messengers. He was also involved in the creation of the world. He is honoured, being mentioned along with his most prominent helpers, in daily prayers; but is not the sole, or even primary, focus of Mariy religiosity.

So what, and who, are these bloodthirsty gods worshipped in the groves? There is no standard enumeration; deities are often local or regional, holding sway over a certain region, or only honoured by a specific grouping of people. The major deities, however, are respected by all the people. The foremost of these is the ‘Great God’, Kugu Yumo, an ancient deity who somewhat resembles the god of the monotheistic faiths. He is seen as all-knowing and all-seeing; though these attributes, it should be noted, are also attributable to pre-Christian deities such as Odin in Scandinavia, who could see the whole world by means of his raven messengers. He was also involved in the creation of the world. He is honoured, being mentioned along with his most prominent helpers, in daily prayers; but is not the sole, or even primary, focus of Mariy religiosity.Beneath Kugu Yumo comes a pantheon composed of the spirits of important physical objects, such as the gods of the sun, of the wind, of the forests and of the fields. Also included are the gods of important concepts, such as fate, oaths, and creative energy. As such, the religion is essentially animistic, attributing personalities to all the things of the world with which people will be required to relate, and allowing them to interact with these spirits by means of sacrifice. Animism can be understood as a religion based on the idea that all things- human, animal, or even inanimate- possess a discrete soul, or spirit. There are, in most enumerations, nine higher gods beneath Kugu Yumo; though the exact identities of these deities show some variation from list to list.

Religions to which the Mariy religion can be most easily compared include Japanese Shinto and Indian Hinduism. Shinto is also a survival of animism into the modern era, basically constituting the worship of nature. Where it differs from the Mariy faith is in the standardised, unitary nature of its pantheon, cemented by centuries of nationalist ideology. The diversity of Mariy deities more effectively mirrors the situation found in Hinduism, where an enormous number of local spirits are worshipped without the diversity threatening the unity of the religion over-all.

This, then, is the basic shape of the Mariy traditional religion. It exists both as a pure religion in its own right, and also mixed with Christianity to various degrees in syncretistic hybrid cults. There also exists a current within the Mariy religion, most effectively expressed in the writings of Popov and Tannygin (the latter himself a Kart), that is attempting to introduce a mystical schema similar to that found in some outside traditions into Mariy religion. In their presentation, the higher gods are viewed as hypostases of Kugu Yumo, who is seen as an emanational force under-pinning existence in a fashion reminiscent of the role attributed to Vishnu or Shiva in sections of Hindu tradition, or even of the neo-Platonic thought of late Roman paganism. While this tradition represents a modern intellectualisation of Mariy tradition, it is, nonetheless, an authentic outgrowth of that tradition and must, as such, not be dismissed out of hand. It may, if its creators succeed in their mission of standardising the faith, represent the future of Mariy religion.

So what, then, does the future hold for Mariy heathenism? The present situation of the Mariy people is, in many ways, a difficult one. They are currently a minority even in their titular homeland, the Mariy-El republic. The administration of that region is currently in the hands of the party of radical Russian Nationalist Vladimir Zhirinovsky, a man whose ideology includes a mixture of the fascist and the bizarre. As such, the human rights position in Mariy-El is far from ideal; in May 2005, the European Parliament even went so far as to pass a resolution sharply criticising Russia for the lack of basic rights accorded to the Mariy people. Activists in Mariy cultural organisations have been beaten up, and the previously mentioned Kart Vitaliy Tannygin has been arrested and imprisoned for allegedly promoting religious discord.

So what, then, does the future hold for Mariy heathenism? The present situation of the Mariy people is, in many ways, a difficult one. They are currently a minority even in their titular homeland, the Mariy-El republic. The administration of that region is currently in the hands of the party of radical Russian Nationalist Vladimir Zhirinovsky, a man whose ideology includes a mixture of the fascist and the bizarre. As such, the human rights position in Mariy-El is far from ideal; in May 2005, the European Parliament even went so far as to pass a resolution sharply criticising Russia for the lack of basic rights accorded to the Mariy people. Activists in Mariy cultural organisations have been beaten up, and the previously mentioned Kart Vitaliy Tannygin has been arrested and imprisoned for allegedly promoting religious discord.A further challenge comes from the resurgent Christian religion. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, evangelical protestant missionary groups have attempted to make inroads into remnant pagan populations. They have a presence in Mariy-El at the moment, though their mission has not yet met with extensive success. The Orthodox Church of Russia, too, is making its presence felt; Bishop Ioan of Yoshkar-Ola has criticised modern Mariy religious gatherings as ‘occult perversions of traditional paganism’.

The extent to which the other religions of Russia are able to act against Mariy paganism is, however, limited by the terms of the 1997 law on religion. This legislation states that religions ‘constituting an inseparable part of the historical heritage of Russia's peoples’ must be respected. More, it specifically includes among such religions ‘ancient pagan cults, which have been preserved or are being revived in the republics of Komi, Mari-El, Udmurtia, Chuvashia, Chukhotka and several other subjects of the Russian Federation.’ Due to the terms of this legislation, Orthodox priests decrying the Mariy religion are subject to imprisonment. They would, in fact, have committed the same offence for which Vitaliy Tannygin was arrested. The argument of Tannygin’s accusers was that he over-stepped the very mark that in other circumstances protects the Mariy, claiming his religion was superior to all others, and potentially exacerbating religious-ethnic tensions in Mariy-El.

The legal situation thus ensures that dealings between religions are forced to retain a degree of mutual respect and toleration. Whatever may be said of the character of the provincial government, or the state of human rights in Russia in general, it must be admitted that such legal protection means that the situation for the Mariy heathen religion is currently better than it has been at almost any time in the last few centuries. Under Communism, Mariy religiosity was repressed by the prevalent state ideology of atheism. Under the rule of the preceeding Tsarist regime, Orthodox Christianity was the state religion, and forced baptism campaigns were conducted against the Mariy. The people were forced to pay for the upkeep of churches in which they did not wish to worship, and faced imprisonment and deportation to Siberia if they were caught practicing their native traditions. This is now, definitively, no longer the case.

So will the Mariy religion experience a resurgence in the new, liberal environment? Not if it does so by attaching itself to an anti-Russian, nationalist agenda. The legal protection that has been given can easily be removed, should the Russian state deem it in its interests to do so. It is well-known that the Russian government is hostile to separatist nationalism in its constituent republics, as Chechnya has so amply proven. On the other side of the coin, stoking up the fires of nationalism could help to breed an environment of inter-communal hostility that might, given time, transform the ethnic mosaic of the Volga Bend into a northern version of the Balkans. Such an outcome is, from all perspectives, one to avoid.

So what is the alternative? In many countries, different religious traditions have a long history of co-existence; in China, Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism have rubbed along side-by-side since the first millennium; and in Egypt Islam and Coptic Christianity have maintained peaceful relations since the 7th century Arab conquest. If mutual respect between traditions can be maintained, there is no reason that the religions of the region cannot all survive. If this is the case, then the unique tradition of the Mariy may yet prove a resource for that people to deploy in their efforts at future development. It is easy to imagine tourist interest arising in the sacred groves, and curiosity on the wisdom of the Karts arising in lands further west. If such potential can be translated into actual visitors and the arrival of tourist dollars, then the poverty that blights the republic of Mariy-El could be, in part, alleviated. It would be a wonderful thing indeed if the oldest, most repressed parts of the Mariy culture could be the engine that drives their future economic salvation; whether this will be so is in the hands of the Mariy themselves, of any westerners willing to trail-blaze the region, and, as the Karts might remind us, of the gods.